“So My Kid Has Diabetes, Now What?”

Your Child Will Be OK: If you are reading this page, you have probably recently found out your child has been diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes. Like we were, you are nervous for your child and your family, overwhelmed with information and wondering how all this is going to work. Many of our first questions were about the basics. What does this mean for our child? Is he or she going to live a full life? Will he or she be able to run around and be a kid and ultimately be able to lead a normal life, have children? As hard as it is to do, you really have to sit down and take a deep breath. This is scary stuff. The good news however, is that although your child has diabetes, they should be able to lead a happy, healthy and normal life. Their life will be governed by a regimen that they will need to follow to ensure that they get the insulin they need and that they keep their blood sugar under control, but assuming that they follow this regimen, they should lead full and productive lives.

It took us awhile to get to this realization. During our initial hospital stay, our endocrinologist did not have the best bedside manner, so many of the reassurances we were seeking were met with very clinical answers that contained enough caveats that the hospital attorney would have been proud. We then turned to the internet of course. There are plenty of search results that come up for diabetes using any search engine, but unfortunately, the internet is filled with information that is not particularly helpful. A lot of the information out there is about Type 2 diabetes, since Type 2 diabetes accounts for approximately 90% – 95% of all diagnosed cases of diabetes in the U.S. (which is why we started www.mykidhasdiabetes.com!) After some time however, and after additional internet searching up until the early hours of the morning, speaking with other parents of diabetic kids and talking to more doctors and nurses, we ultimately came to the realization that our little boy was going to be ok. This allowed us to focus on how we were going to incorporate this new regimen into our daily lives. We will get into my recommended first five steps to take to get this regimen under way in the coming chapters.

Misinformation overload and unhelpful conversations

Having a kid with diabetes is like the old saying, if you have a red car; you start to notice that everyone else has one too. Once word gets out about your child’s diabetes, the phone calls or emails are likely to come pouring in from well meaning friends and family. More often than not you will hear, “if you ever feel like talking to someone who has a child that has diabetes, my neighbor has a teenager that has had it since he was four, and they are VERY involved in the JDRF (Juvenile Diabetes Research Fund) and do that walk they do every year. I am sure I can set you up to speak to them.” The first few of these are welcome referrals and we actually did take a few of our friends up on the offer. After the tenth or fifteenth of these however, you tend to say thanks very much, appreciate you thinking of us. We did find the few quality discussions we had with other parents helpful. It made us realize that everyone approaches being a caregiver for the child differently, but there are some helpful ideas that come out of any of these conversations. Take what you want out of them, don’t treat them like gospel for sure.

The more unfortunate conversations are those that include some of the following, “so sorry to hear your child has diabetes, is he overweight?” or “I have some great sugar free recipes I can send you” or my “father has diabetes, we keep telling him he needs to lose weight and exercise more, I guess you will need to get Billy enrolled in some sports programs or something”. All of these comments are not helpful for a number of reasons.

Reasons to Tune-out Unhelpful Comments and Advice

Reason One

Most of these types of comments are derived from a misunderstanding of the difference between Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes. As you likely know by now from your early conversations with you pediatric endocrinologist, Type 1 diabetes is caused by the destruction of beta cells of the pancreas that produce the insulin necessary to regulate blood sugar levels. Type 1 occurs predominantly in children or before the age of 30 and is often referred to as juvenile diabetes or insulin dependent diabetes. Type 2 diabetes commonly occurs after the age of 40. In Type 2, the body does produce some insulin, but the amount is either not sufficient or the body is not able to make proper use of it. Type 2 diabetes is generally controlled by diet, exercise and/or tablets and is often closely linked to obesity. Although some people in this group will use insulin injections, it is sometimes referred to as non-insulin dependent diabetes. There is a lot of confusion about the two types, and we tried to block out such unsolicited advice.

Reason Two

These types of comments can often imply that somehow as parents, you were responsible for your child getting diabetes by not feeding them the right things or that you didn’t allow your kid to get enough exercise. None of that is true. Why kids get diabetes is still a bit of a mystery. The current studies indicate that Type 1 diabetes is caused by a virus our auto-immune disorder in kids with a genetic predisposition for the disease, which bottom line means, this is not your fault.

Reason Three

A lot of these types of comments from well meaning folks tend to also make you feel a bit isolated and that people don’t understand what your child has or what you are going through. We went through this brief phase, but there is an incredible, helpful community of parents, fellow diabetics, volunteers and organizations that ultimately make you feel like you are not alone and that you child will always have the support of the diabetes community as he or she grows up and learns to follow the regimen of diabetes on their own.

How are we going to deal with this on a day to day basis?

Once we realized that our child was going to be ok, our focus then turned to logistics. How were we going to be able to cope with testing our son’s blood sugar and administering him insulin 7-10 times a day? He was nervous about flu shots once a year, now we had to go through that every day? How was he going to be able to go to school? Would the school be able to handle testing his sugar and giving him insulin? The logistics around testing and insulin alone seemed overwhelming, never mind the need to try and figure out how many carbohydrates are in everything he eats, particularly when none of the food packaging shows serving sizes that are even close to the quantity of what he eats. HELP!

The good news is that it gets easier. The testing and insulin administering will become second nature and your child will learn to roll with the regimen. That may be hard to see now, but you will become a pro. Hopefully the tools and tips provided on this site and elsewhere will help accelerate that process.

Regarding School

Every school is different and your specific circumstances will vary, but the good news is that the right for your child to receive care for his or her diabetes is protected at the federal level. Children with diabetes have a right to care for their diabetes at school based upon the Individual with Disability Education Act (IDEA) and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. These laws, among others at the state level, provide protection against discrimination for children with disabilities, including diabetes. Bottom line is that you have rights and most schools have figured it out that they need to be set up to take care of managing your child’s glucose levels while at school, including testing and administering insulin to your child during school hours. Your regional JDRF can be very helpful in navigating the situation with local schools.

The First Glucose Tests and Insulin Shots

For us, the first glucose tests in the hospital were done with lancets that looked like steak knives and the shots of insulin our child received in the hospital were with needles that looked like they were from the 1960’s. What made matters worse, was that these were administered by the “overnight” nurses that had little to no bedside manners and they wanted us to hold our three year old child down so she could administer the shot. This was not going well and it added to our anxiety about the fact that we were going to have to do this every day going forward for a very long time. Fortunately, the daytime nurses were much better and once we got a chance to talk with the pediatric nurse practitioner, we were able to ask whether all the needles and lancets were so big (and scary). She quickly admonished the hospital staff for using the older supplies and made sure that we were provided with updated supplies, which included lancets that were as close to pain free as a shot can be, i.e. they did not produce tears, and needles that were a fraction of the size of what had been used on him at first.

Bottom line, do not let your experience in the hospital negatively color your view of how this will go in the future. Apparently, despite the progress in needle technology and size, all hospitals don’t use the latest supplies and all nurses are not necessarily schooled in the kinder, gentler approach to interaction with their pediatric patients. Nurses are wonderful, dedicated professionals, but they see lots of patients and they can only work with the supplies they are provided. Plus, this is all new to both you and your child and you both will get used to the lancets and shots so that it becomes routine.

Bottom line, do not let your experience in the hospital negatively color your view of how this will go in the future. Apparently, despite the progress in needle technology and size, all hospitals don’t use the latest supplies and all nurses are not necessarily schooled in the kinder, gentler approach to interaction with their pediatric patients. Nurses are wonderful, dedicated professionals, but they see lots of patients and they can only work with the supplies they are provided. Plus, this is all new to both you and your child and you both will get used to the lancets and shots so that it becomes routine.

You will likely be asked to administer the tests and shots yourself while you are still in the hospital. Take advantage of this time to try it out. Our boy was pretty tough throughout this whole ordeal, so we were lucky. One thing we did that we found helped a lot is we tried to treat our child in a way that we would want to be treated. We told him what was going on and he became part of the process. Ultimately, our child ended up calling his shots “whatevers”, because every time we gave him a shot it was like, whatever. They get so used to it that we would give them to him while he was watching TV and he never took his eyes off the show or acknowledged that we were giving him insulin.

How are we going to pay for this?

If you are enrolled in private group health insurance through your employer, and your child is a dependent on that policy, it is likely that the insurance will cover all or at least a substantial portion of the cost associated with your child’s diabetes. Even in small and individual market health insurance policies, most states provide that these policies must cover diabetes supplies, services and medications. If you do not have private group health insurance, or have not been able to secure an individual policy, there are many alternatives that will likely provide your child coverage.

If the reason you do not have insurance is that you recently lost your job for example, you will be eligible for COBRA coverage. COBRA permits some employees and their dependents to continue on an employer’s group health plane even after coverage would otherwise end. Certain states also provide for state continuation coverage if you worked for an employer that had less than 20 employees, or you may also have the right to convert your coverage to an individual policy, often called conversion coverage. The recent Affordable Care Act also eliminates pre-existing conditions starting in 2014. No more pre-existing conditions means you can’t be denied coverage, charged more, or denied treatment based on health status. You should seek some guidance on getting the right coverage, but most plans tend to have pretty good coverage for diabetes and the supplies you will need on a daily basis.

What is the Deal with all the Math?

Math will become your new best friend as you dive into your daily routine with diabetes. Don’t worry though, it gets easier and getting organized and set up with the right tools will help make the daily calculations part of your daily routine. If you end up using a pump, a lot of the math calculations end up being done for you in the pump unit, but we were very glad that we used insulin pens for the first year because it really allowed us to understand the various calculations. Here is a quick summary of the various metrics with which you will become intimately familiar.

Carb Ratios / Correction Factors and Target Glucose Levels

Once you get with your pediatric endocrinologist, they will give you numbers that will at first, feel a bit daunting. This will include carb ratios, correction factors and target glucose levels that are specifically customized for you child. Eventually, these metrics will get refined so that you may have different metrics for each part of the day or meal as your child’s routine, and daily cycle and absorption rate of insulin may vary during the day,

Carb Ratio: The carb ratio is the number of units of insulin that gets administered (by injection or pump). The resulting figure from dividing the total # of carbs to be eaten by the carb ratio provided by your doctor (i.e. 70 carbs to be consumed divided by a carb ratio of 16 would result in 4.4 units of insulin), will only “cover” what your child is going to eat (i.e. offset the sugar created by the carbs they eat) and is only part of the total insulin calc.

Correction Factor: The second part of the calc has to take into account what your child’s current blood sugar levels are, i.e. if they are too high, more insulin will need to be added to bring these levels down to your blood sugar level target (ours has ranged from 120-150 depending on the time of day).

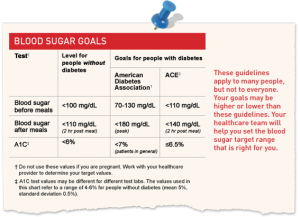

Target Glucose Levels: Your doctor will come up with your initial glucose level targets. Our doctor started out with an initial target of 150 mg/ dl and we worked with her to refine it from there. We generally have a target now (for our seven year old) of 120 mg/dl.

The Final Formula: The final formula therefore for determining insulin dosage is as follows:

(grams of Carbs / Carb Ratio) + ((Glucose Level-Target) / (Correction Factor))

Said another way, divide the grams of carbs to be eaten by the carb ratio to get the insulin related to food to be eaten, then calculate the difference (if any) between your child’s current glucose level reading from the meter and your target glucose level, and divide that result by the correction factor. Add the two resulting units of insulin together and voila, you have the amount to be injected. We set this math up on our workbook in excel on our kitchen laptop so it did all the math for us each time. This made it easier for us and made it easier for babysitters, parents and other caregivers.

Basal vs. Bolus

Bolus: The insulin calculations discussed above all relate to administering a bolus dose of insulin. A bolus dose is insulin that is specifically taken at meal times to keep blood glucose levels under control following a meal. Bolus insulin needs to act quickly and so short acting insulin or rapid acting insulin will be used.

Bolus insulin is often taken before meals but some people may be advised to take their insulin during or just after a meal if hypoglycemia needs to be prevented. Your doctor will be able to advise you if you have any questions as to when your bolus insulin should be taken.

Basal: The role of basal insulin, also known as background insulin, is to keep blood glucose levels at consistent levels during periods between meals or “fasting”. When fasting, the body steadily releases glucose into the blood to our cells supplied with energy. Basal insulin is therefore needed to keep blood glucose levels under control, and to allow the cells to take in glucose for energy. Basal insulin is usually taken once or twice a day depending on the insulin. Lantus is an example of a Basal insulin. Basal insulin needs to act over a relatively long period of time and therefore basal insulin will either be long acting insulin or intermediate insulin.

A Basal / Bolus regimen is typically used when utilizing insulin pens. When using a pump, background insulin is administered constantly by the pump, and therefore injecting a once daily Lantus or similar long acting insulin is not typically necessary.

Next Steps

We hope the information above has been helpful, a lot of it you may know already, but it is based on our experience and some of it may differ from what you will encounter. Check out our “First Months” tab for Five Initial Steps to getting organized in the early days of caring for you child.